Anyone who knows the frenzy of March Madness should understand that college sports are big business. Between ticket sales and lucrative licensing deals that allow for televised game coverage and profitable merchandise revenue streams, college sports is a billion-dollar industry.

Businesses, of course, have employees. Yet, for far too long, the NCAA and its member schools have pretended that the athletes who drive the demand for their product are something other than workers. Their pretense is galling in light of example after example that coaches and administrators directly profit off of players, like Ohio State University’s athletic director who just received an $18,000 bonus because a single wrestler won a national title.

That charade is finally starting to fall. Chicago’s NLRB Regional Director Peter Ohr ruled this week that Northwestern University (NU) scholarship football players are in fact employees who have the right to organize because they are paid to play football through scholarships and assorted stipends and under the control of the school, their employer.

This isn’t final, however. Northwestern has vowed to appeal Ohr’s decision to the full NLRB. Any ruling by the Board is sure to then be appealed to the federal courts. However, the comprehensive decision leaves little doubt that Northwestern football players are employees, compensated by the university to play football and directed to spend their time doing so.

In striking fashion, Ohr removed the veneer of college sports, demonstrating in painstaking detail that playing football for Northwestern University is real work. Scholarship players sign legal contracts stipulating that they will follow the direction of the school’s coaches in exchange for tuition and various stipends. These scholarship contracts are largely dependent on a player’s on-the-field performance and fulfillment of team requirements – the school can revoke the agreement for any number of reasons. In other words: No work, no pay.

Just what kind of control does the school maintain over the players? Scholarship athletes are not allowed to miss practice during the regular season, even if it conflicts with a class. Even in the offseason, football is the priority. Northwestern’s starting quarterback Kain Colter testified under oath that coaches “discouraged” him from taking a required chemistry class for his pre-med major because it conflicted with morning workouts. Missing that class put Colter behind his peers in the pre-med program and he eventually changed majors.

The type of catch-22 that Northwestern puts upon its football players – choosing between their job or their education – should sound familiar to workers in other types of precarious employment. Walmart associates often report being directed to schedule their lives around their work or risk losing their jobs.

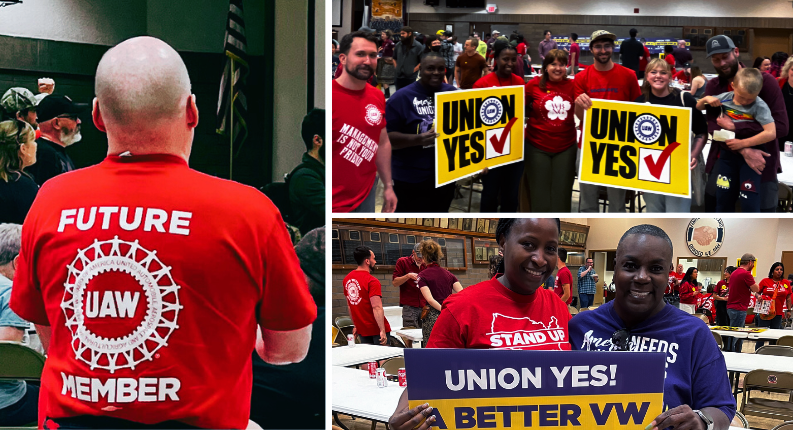

It’s no surprise that college football players want to form a union and gain a voice on the job. Collective bargaining would offer NU players a chance to have a say over the terms and conditions of employment. Indeed the players and their union, the College Athletes Professional Association, have shared their priorities in collective bargaining, which include greater attention to sports-related traumatic brain injury, coverage for sports-related medical expenses, improved graduation rates, and compensation for the use of their likeness in commercial sponsorships. (Remember the players don’t see a single cent from the $60 jersey fans wear at games.)

Ultimately all of us – fans, students, alumni and workers’ rights supporters – should be rooting for college athletes in their fight for formal recognition as employees and the related right to organize. Collective bargaining will bring greater accountability to college athletic departments, which typically shield their multimillion-dollar budgets from public scrutiny. It will finally require the NCAA and college administrators to answer for creating a system that enables them to profit off of unpaid labor.