At first, companies like Uber were hailed as “disrupters” and “innovators” that would change not only the way we purchase goods and services, but also how we work and earn income. Now, holes are starting to show in the fabric of the “on-demand” economy business model.

Until recently, there was very little data about Uber and the “on-demand” economy as a whole, aside from some valuation estimates and corporate-provided calculations of the number of people working through their platforms. However, nothing that either confirmed or refuted these companies’ claims about their business models existed.

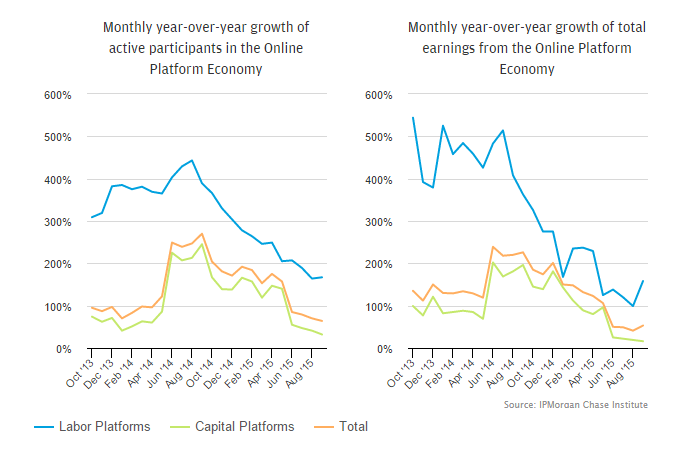

Like many other businesses, Uber and other “on-demand” economy ventures rely on rapid growth in new markets to drive their bottom lines. But in a first-of-its-kind study, the JP Morgan Chase Institute analyzed the income of thousands of users of labor platforms such as Uber. The study found that while the workforce of “on-demand” companies soared between October 2013 and October 2014, the years since have seen a marked decline in the rate new people are signing up to work for these companies.

This decline could be because on-demand companies are making the people who work for them do more for less. Take ride-hailing corporations Uber and Lyft, for example. Many Lyft and Uber drivers were encourage to buy or lease new cars through lending programs provided by the companies themselves. But now these drivers are having a hard time paying for the cars because of mandated fare cuts (AKA pay cuts). Meanwhile their car payments remain sky-high. So drivers are saying “enough is enough” and coming together to fight for a fair return on their work. As for Uber’s public promises of decent wages, Angelica, an Uber driver in San Francisco said, “Some things really are too good to be true.”

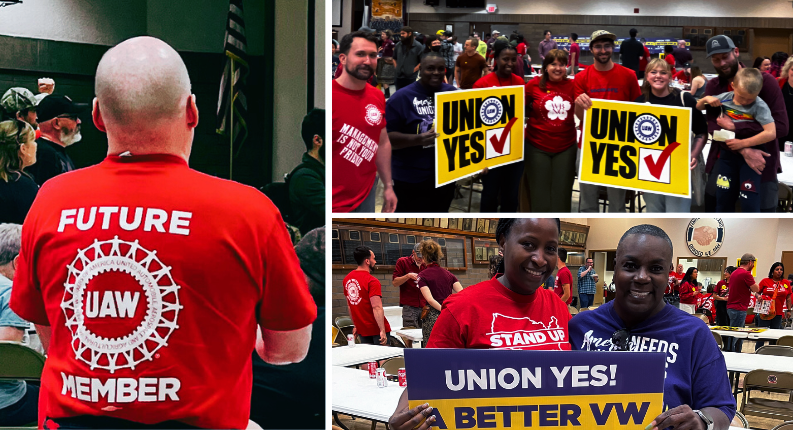

These driver-organizing efforts are coming to a head in Seattle, where the city council recently enacted rules establishing a legal framework for Uber and Lyft drivers to organize unions. These drivers are typically excluded from the protection of federal labor law because Uber and Lyft claim their drivers are independent contractors and not technically employees. Misclassifying employees as independent contractors is not an innovative labor policy that Uber and Lyft cooked up. It’s a decades-long scheme by unscrupulous companies that don’t want to take any responsibility for the people who make their businesses run.

Faced with drivers who are coming together to confront its exploitative business model, Uber is turning to traditional big-business unionbusting tactics, like enlisting customer service representatives in their effort to dissuade drivers from having a say over their jobs and tapping the Chamber of Commerce to block Seattle’s new ordinance from taking effect.

As long as we treat companies like Uber as unique disruptors, we are destined to turn a blind eye to their questionable corporate practices. But if we take their multimillion-dollar lobbying efforts and evasion of legal responsibilities seriously, we see that Uber and its peers are just new corporations using old techniques to maximize profit. With the veil lifted, we can follow Seattle’s lead and set standards to make sure the working people who are the engines behind these companies’ growth can lead a good life.

hmm

they sell us the knives we hold to each others throats