This past January, the insurance giant Aetna announced that it would raise its minimum wage to $16 an hour, and in late April, these raises finally made it into its employees’ pockets. As part of an effort to reduce the stress faced by front-line customer service associates in addressing their basic living expenses, Aetna also announced that it would reduce the out-of-pocket healthcare expenses for its lowest-paid employees.

The Hartford, CT, based-firm isn’t alone in raising the pay of its workforce this year, as The Gap, TJMaxx, and Target have made headlines for upping their pay scales for starting employees. Aetna is certainly taking a much more significant step than corporations such as McDonald’s, which only increased pay for less than 10 percent of its workforce, or Walmart, which announced a paltry minimum wage increase to $10 an hour by early 2016.

Aetna is even setting the pay for its lowest-paid employees to a level above the newly-introduced Congressional proposal for a federal minimum wage of $12, and above the $15 an hour demand of fast food clerks, home healthcare aides, baggage handlers, and Walmart associates.

The insurer’s decision came as a result of executives exploring the challenges its workers faced, and recognizing that its previous level of pay, which started at $12 an hour, was simply not enough for its employees to support a family without having to rely on social safety net programs such as Medicaid and SNAP (supplemental nutrition assistance program – commonly known as food stamps).

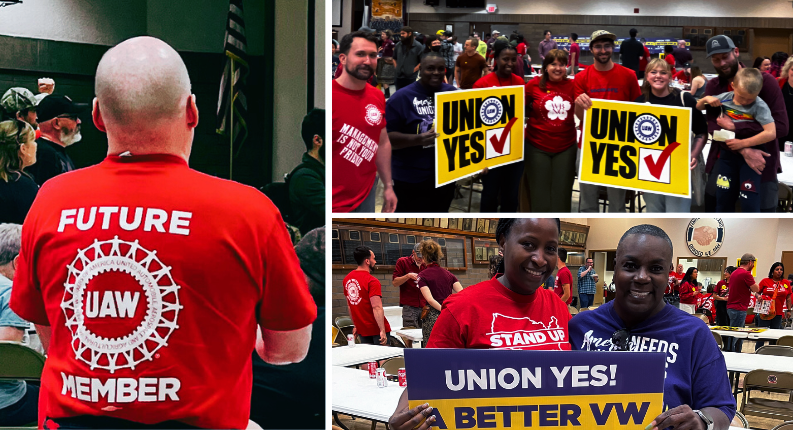

In a recent commentary in Fortune, Jeff Furman, Chair of the Ben & Jerry’s Board of Directors, praised Aetna’s decision to raise wages. Furman rightly viewed the sweeping protests on April 15, where Americans united in a collective demand for jobs paying at least $15 an hour, as a milestone effort for “Getting employers to see the value in caring for their employees and ensuring they can lead a dignified life.”

As Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini explained in an interview with NPR, he was alarmed “that we as a thriving organization, as a successful company, a Fortune 100 company, should have people that were living like that among the ranks of our employees. We wanted people at the front lines who took care of our customers to not have the kind of stress associated with being able to provide health coverage for their families and food for their families, worrying while they were on the job.”

A recent New York Times editorial points out the fact that three out of every four families who receive this critical state assistance are headed by someone who works. The Times elaborates:

“The problem is that as labor standards have eroded, allowing profitable corporations to pay chronically low wages, taxpayers are not only supporting the working poor, as intended, but also providing a huge subsidy for employers by picking up the difference between what workers earn and what they need to meet basic living costs. The low-wage business model has essentially turned public aid into a form of corporate welfare.”

Indeed, according to a new report, working families access these programs at a cost of more than $150 billion annually to federal and state governments. And it is middle class families who subsidize these big, highly-profitable corporations by paying for health care, child care and other critical services when workers don’t get paid enough to get by.

In an effort to hold corporations accountable for low-wage jobs, some communities are turning to innovative solutions. In Connecticut, for example, Jobs With Justice is part of a coalition working to advance SB 1044, which will charge big businesses a fee when they do not pay their employees a worthy wage. The revenue collected from this fee will then go towards the $486 million worth of services that working moms and dads in Connecticut rely on when their paychecks simply aren’t enough.

It’s good to see a large corporation like Aetna take responsibility for its practices and recognize the effects that low pay has on families. But for other profitable businesses, there is a choice that must be made. They can either start paying their employees’ decent wages, or they can pay local governments to cover the health care, child care and other costs that working families need to survive and thrive.