Redlining. Predatory lending. Evictions. Housing practices, based on structural racism and in service of white supremacy, continue to determine who gets a home and where. Over the coming weeks, the United States will face a housing crisis deeper than any seen in the last hundred years, one that will once again exact a disproportionate toll on Black and Brown people.

A confluence of events put up to 23 million renters, one-fifth of the nation’s renters at risk of foreclosure or eviction by the end of September. Without an extension, the $600 a week emergency unemployment supplement will expire by the end of July. Most eviction prohibitions at the federal, state, and local levels will lapse, and alongside the re-opening of local housing courts put millions at risk. Combine those with the continued threat of job losses, as many places in the United States roll back re-openings to combat a surge in COVID cases.

Some states have temporarily extended eviction moratoriums, as has the Federal Home Loan Agency (but only for renters of single-family homes which have federally guaranteed mortgages), which will protect small numbers of renters by deferring the crisis they face by a few months.

Since during the moratorium, rental payments have been deferred, not canceled, millions will have to come up with thousands of dollars of back rent in order to avoid evictions.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic wrecked the livelihoods of millions, an evictions crisis had its grip on renters across the country. Every four minutes, someone was evicted in the United States. And that was before the pandemic. The cascading of the impending crisis will dramatically increase this rate.

Evictions have lasting effects that make it much harder to find housing in the future, contribute to job loss, and reduce children’s economic opportunities as evicted families tend to move to more marginal neighborhoods in communities. “Eviction is not just a condition of poverty, it is a cause of it,” says Evictions Lab housed at Princeton University.

Several things were different during the last housing crisis that started in 2008. First, there was no pandemic, meaning the tragedy of losing one’s home was not compounded by immediate threats to health and life. The other major difference is far less of the nation’s rental units were owned by networks of corporate landlords.

In the wake of the deep housing-led recession of 2008, millions of American families lost their homes to foreclosure and their apartments to eviction. In 2012, the federal government launched a pilot program that incentivized Wall Street investors to easily buy foreclosed homes held by the government’s mortgage financing agencies. Government-owned Fannie Mae guaranteed $1 billion of Blackstone Group’s loans used to acquire 50,000 homes for its Innovation Homes business. Between 2011 and 2017, hedge funds, private equity firms, and other deep-pocketed investors snatched up more than 200,000 homes, paying $36 billion.

Today, this new pernicious breed of corporate landlords, firms like industry giants Cerberus (and their FirstKey Homes subsidiary), Lincoln Property Company, Greystar Real Estate Partners, Starwood Capital and Equity Residential and dozens more, collectively control more than a million units of America’s rental units. Today, nineteen corporate landlords that rent apartments, each having more than 50,000 units, control nearly 1.2 million apartments together, while the top 5 corporate landlords renting single-family homes control more than 200,000 housing units. These large corporate landlords are more likely than smaller landlords to evict their tenants, according to a study by the Federal Reserve Board of Atlanta. These giant players have all prospered not only from the fire-sale prices at which these properties were acquired but from rents that have increased faster than inflation over the last decade, taking an ever-greater cut of workers’ paychecks.

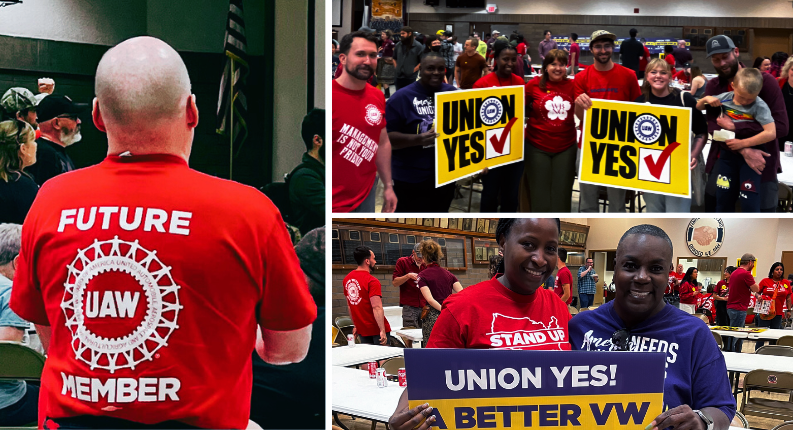

With this concentrated wealth comes outsized political power. That’s why rent strikes organized by Jobs With Justice and others are calling on large corporate landlords to use their political power for the common good, demanding that Congress require the cancellation of rents and mortgage payments as a condition for any bailout aid for the financial service industries.

There is a long history of the government in the United States ensuring that people are protected from losing their housing in times of crisis. People have demanded, and states have often enacted foreclosure, debt collection, and other moratoriums throughout American history from the time of Shays’ Rebellion in the 1790s through the Great Depression. More recently, the federal government created the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP), which allowed homeowners impacted by the 2008 housing crisis to restructure the terms of their mortgages without penalty. Similar programs could be established to assist small landlords with the costs of foregone rents. But relying on the national or even state and local governments is a difficult process that requires navigating pitfalls in all branches of government. Working people will have much more leverage to navigate these pitfalls if rent strikes against Wall Street landlords impact their bottom line.

In April, Jobs With Justice and many of our network partners, joined the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) and others in calling for a National Rent Strike, to build collective power and demand that government take the first steps to moving housing from where it is today: a profit-driven commodity heavily controlled by private equity, hedge funds and Wall Street banks, to what it should be: a fundamental human right that undergirds human security and dignity.

We have written to 45 top corporate landlords with a demand that they forgive rents for those who can’t pay due to job loss, or COVID-related illness or caretaking responsibilities. We have demanded suspension of eviction activities, and called for those continuing evictions to publicly report on steps they’ve taken to prevent implicit race or gender bias in eviction decisions. We’ve heard from one corporate landlord, American Campus Communities, that they have a commitment that none of their tenants will lose their housing during the pandemic, on the basis of not being able to pay. As of late April, they had forgiven $17 million in rent. While the remaining corporate landlords have not responded to our demands, thanks to valuable research by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, we do know that many, including Greystar, and Starwood Capital continued to file for evictions even while the federal moratorium and many state and local moratoriums were in place through the Spring.

There’s much more you can do today:

- Join Jobs With Justice’s call for corporate landlords to cancel rent.

- Learn where your state stands on evictions, then encourage your state and local elected officials to extend eviction and foreclosure moratoriums and support efforts to forgive rents for those impacted by the COVID pandemic.

- Demand that your Congressional representative continue the $600 a week in federal emergency unemployment benefits. These payments have been one of the biggest reasons millions of Americans have been able to remain in their homes despite the loss of their jobs during the pandemic.

- Call your Senators to support Senator Elizabeth Warren’s Preventing Renters from Evictions and Fees Act (S. 4097) which would extend an eviction moratoriums for most U.S. renters through March 2021. The bill has 17 Senate co-sponsors.

- Call local, state and national policy makers to require disclosure of race and gender demographic information in eviction filings. There is strong evidence that suggests that Black women who head households are evicted at twice the rate of white renters, but without systematic reporting of demographic data in eviction filings it is difficult to use the courts to address this unequal treatment.

- Make a gift to Jobs With Justice’s Worker Solidarity Fund, which has gathered more than $200,000 and distributed these funds to hundreds of people and families across the country, for their use in paying rent and putting food on their tables. Many donors have donated their federal COVID relief payments and many more will do so with any future government support payments.