The debate on the need for unions, initiated by blogger Evan Soltas’ call to let them die, has gained considerable attention. On the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s blog, Brad DeLong nicely compiled the back-and-forth – which has grown to include, among others, Kevin Drum, Timothy Noah and Michael Hiltzik.

Soltas, for his part, doubles down on his belief that the United States is better off without unions in his latest entry in the debate. But it’s important to emphasize why that’s not the case.

He uses a paper by scholars Henry Farber and Bruce Western to argue that globalization alone explains declining unionization. Their study relies on NLRB election data, which should give pause to anyone familiar with union elections.

Union elections simply don’t guarantee workers the same basic safeguards and standards one associates with political elections. The NLRB certification process favors employers in close elections, a bias that is greatly magnified under Republican-controlled boards. (For those keeping score at home, Republicans have controlled the NLRB for 20 of the last 34 years, and 16 of the 25 years studied by Farber and Western.) Therefore, despite the best intentions of researchers, the union election data underlying Soltas’ argument is likely biased. At the very least, it doesn’t offer the clear-cut, unambiguous results that Soltas trumpets.

For those familiar with U.S. labor law, this is sadly not a surprise. The absence of financial penalties creates an incentive for employers to violate the law. With increasing frequency and intensity, employers influence union elections in their favor through intimidating and coercive tactics. Such conduct is often unlawful, but still, many unionbusting tactics are technically legal. Employer-initiated procedural delays are particularly effective in quashing union organizing activity.

Barry Hirsch, the author of another paper cited by Soltas to bolster his globalization argument, is careful to note that such a clear inference about the cause of union decline may not exist. Omitted from Soltas’ post is Hirsch’s disclaimer:

“A reasonably coherent story emerges from the empirical literature, albeit one that rests heavily on evidence that is dated and (arguably) unable to identify true causal effects.”

Soltas also claims to be unable to find any research concluding that public policy (i.e. broken labor law) led to the drop in union density. Well, here it is: Studying unionization rate changes from 1960 through 2012, researchers John Schmitt and Alexandra Mitukiewicz find that public policy was a more important determinant than market factors like globalization and technological change.

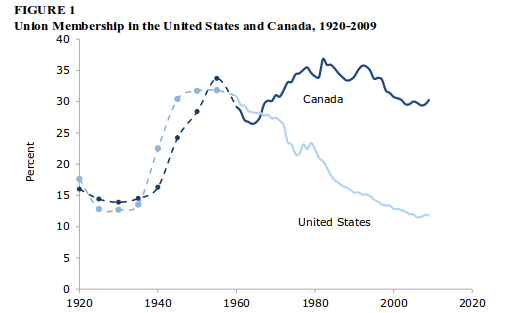

Researcher Kris Warner’s paper on the U.S. and Canada’s differing unionization rates drives home this point. The two countries have similarly structured economies. If globalization really drove the decline in union density, one would expect the membership trends to closely track one another. They do until around the late 1960s and early 1970s. Unlike the United States, though, Canada affords real protections for workers trying to form unions, including a more fair election process. The graph below from Warner’s study illustrates the result of this difference in policy: Canada’s union density rate holds fairly steady, while the U.S. rate drops off. (Demos’ Matt Bruenig elaborates on this research.)

Evidence that policy choices impact a country’s union density makes it hard to believe that the loss of unions in the United States is a foregone conclusion. Globalization and trade may make for an easy explanation of the decline in unions since they are certainly a factor. But dig a little deeper and pay attention to the limitations of the available data, and it becomes clear that the explanation is much more nuanced. More importantly, you see that union decline is fixable. When it comes to saving unions, we therefore have a choice.

Now let’s get back to Soltas’ original question: Are we better off without unions? The answer is no, especially if, like Soltas, we want to improve economic conditions for workers.

Unions serve as a check and balance on employers in the workplace and on corporate power more generally in politics. This benefits all workers, contrary to the picture Soltas paints: lifting union and non-union pay, reducing poverty among union and non-union workers, and limiting wage inequality.

Soltas, though, believes policy makers will support pro-worker policies absent unions. He points to, for instance, the Federal Reserve’s current work to get us to full employment and bipartisan support of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These examples are instructive and, to me, provide evidence of why we need unions.

Policy development, even at the Federal Reserve, cannot be fully divorced from politics. We have Janet Yellen spearheading the Fed’s efforts because Democrats, through the electoral support of unions, control the White House and the Senate. I doubt anyone seriously believes that the Fed would be pursuing these same policies if, say, Greg Mankiw had been nominated by President-elect Romney. Similarly, while I’ve heard Republicans talk a lot about deficit reduction and corporate tax cuts, I don’t recall them promoting an expansion of the EITC until Democrats went all in on raising the minimum wage. And the reason Democrats are rightly doing that is because of the efforts of unions and their members to make addressing wage stagnation and inequality a national priority.

The same will be true of the full employment policies sought by Soltas (and me, and the labor movement.) It takes political power to enact and protect these policies because corporate PACs will oppose politicians who vote to increase worker power. But the labor movement will be there for politicians who support full employment, just as it was in the 1990s.

That’s why the United States needs unions. Fortunately, as the evidence above indicates, they can be saved. Perhaps, therefore, the real question is, are we willing to try? The record suggests we should.

What is our strategy for countering right-wing anti-union propaganda and passing the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA)?

Because the number of union members in the nation is so low(im one by the way) we are depending on friends and family to help spread the word. Via social functions, church,Internet, work place, any where possible.